|

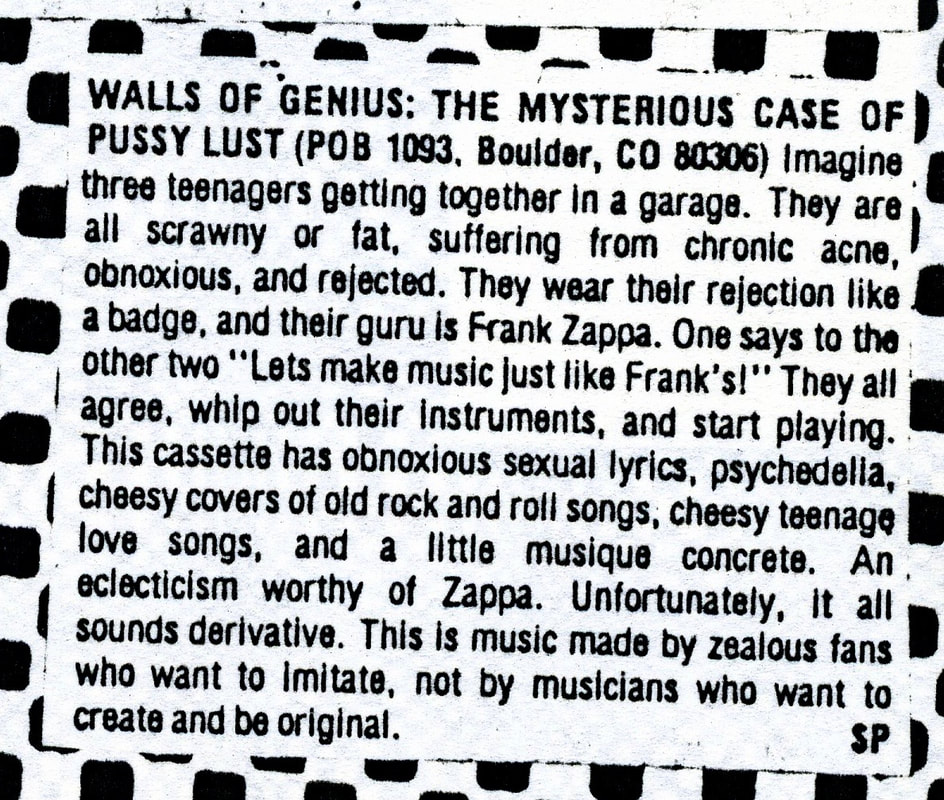

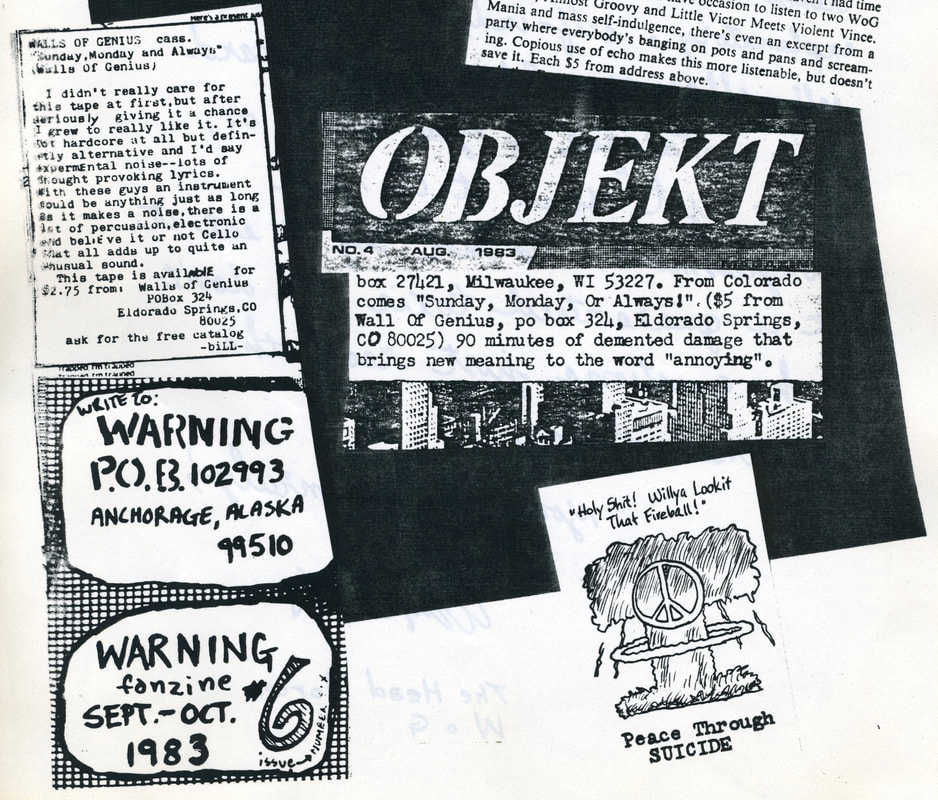

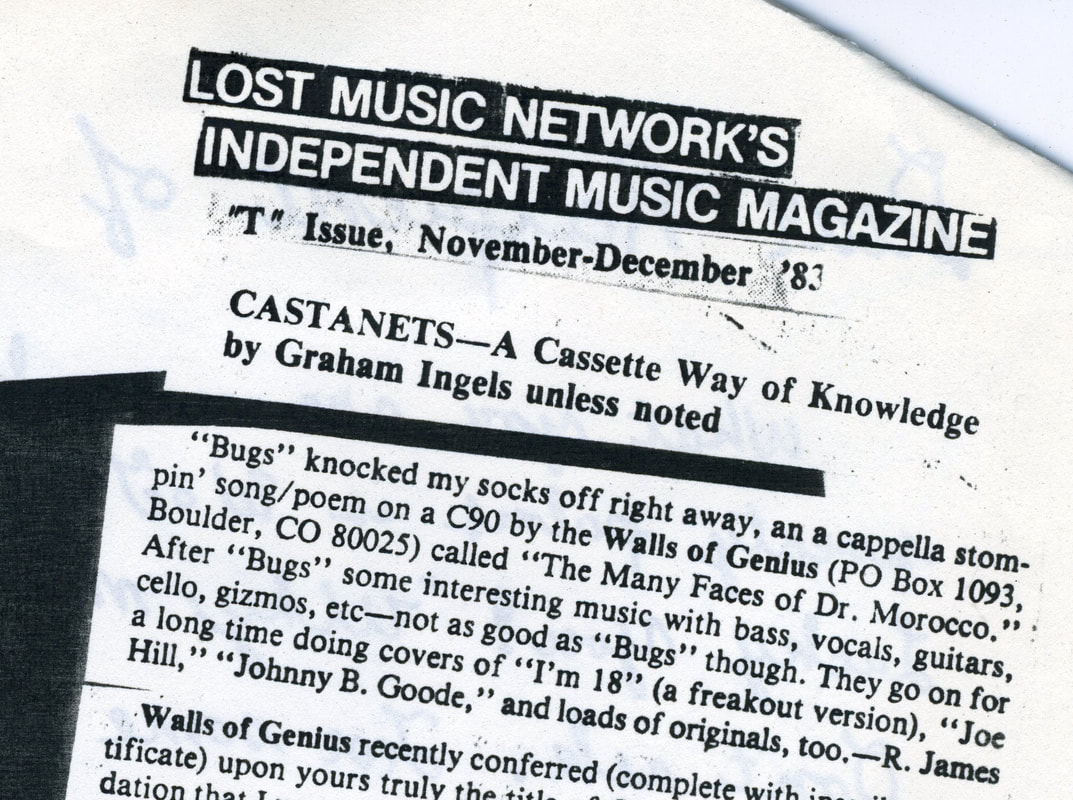

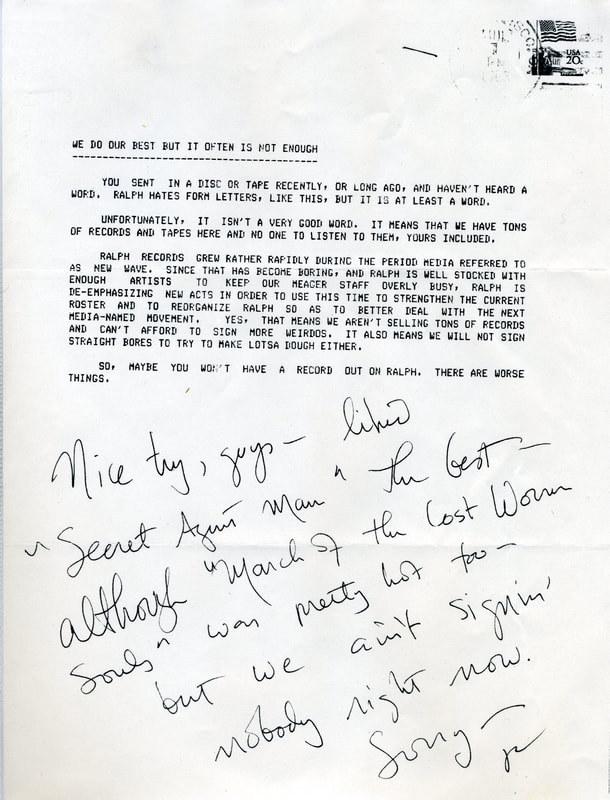

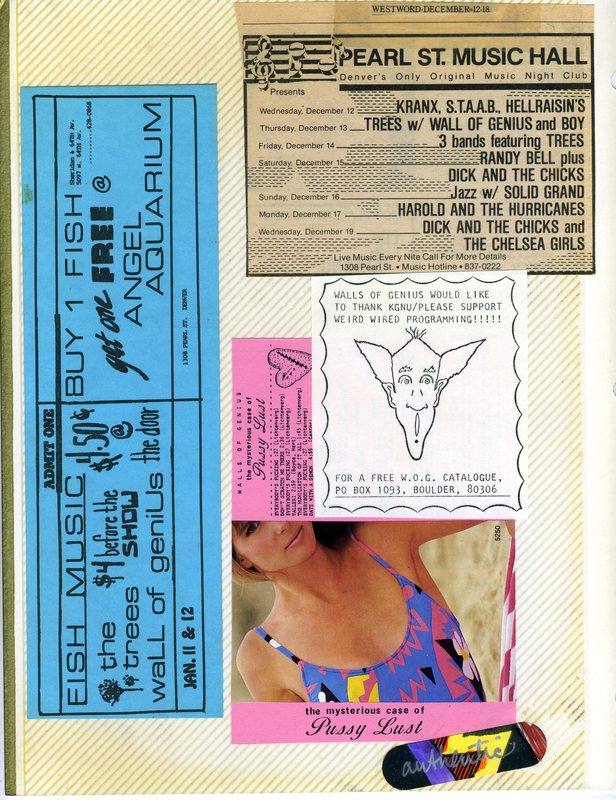

I can remember the feeling of the first time anyone in the alternate media of the 1980s reviewed a Walls Of Genius cassette album. “We exist! We’re for real!” Not all the reviews were un-critical. Although “critique” by definition means critical analysis both good and bad, we mostly associate criticism with negativity. And who wants to be criticized? Haven’t we all had enough of that in grade school, middle school, high school, college, the work place, etc? Like the would-be artist Philip Carey in Somerset Maugham’s Of Human Bondage, we would all prefer a little praise for our work instead of criticism. But most of the time the world doesn’t work that way. When Anne Addison described Walls Of Genius as “the new sound terrorists of America” in the sixth issue of Unsound Magazine, we were overjoyed. But not all of WoG’s reviews were equally enthusiastic. We were also accused of being derivative and sophomoric, as if those were bad qualities. Sometimes they are, but we weren’t worried about wearing our influences on our sleeves and joyfully indulged in low-brow humor. For every listener who was appalled by the idea of sophomoric humor, there was another ready for every laugh, giggle and guffaw. The industrial music folks of the time were particularly serious about their music and Walls Of Genius may have struck some of them as a buffoonish affront. Our efforts, however, were all in the service of satire and parody. Perhaps we had been inspired by Mad Magazine’s 1960’s opus “It’s A Gas”. One of the major tropes of criticism is comparison. “She sounds like Joni Mitchell on a bad trip…imagine Leonard Cohen on speed…etc.” It’s only natural to compare and contrast, a process that can be quite illuminating when attempting to communicate the sound of something solely through narrative. Influences are regularly cited by those writing about music. But sometimes the influence cited is something manifested only in the critics’ mind. Over at the Halls of Genius, we would scratch our heads in wonder. Zappa wannabes? Sorry, none of us were Zappa wannabes. I had owned some Zappa albums over the years, but traded most of them away, realizing that I didn’t really enjoy listening to them. Yes, we had employed sophomoric humor, but it wasn’t Zappa-derived and we were far less scatological. That critic may as well have said we were Mad Magazine wannabes. That would have cut closer to the truth. Most of the time, we were amused and gratified by simply being worth the reviewers’ consideration, even those who didn’t understand us. Critical misunderstanding has got to be the largest elephant-in-the-room when it comes to academic analysis. How many college classes did I sit through where some professor droned on about what the author or artist “meant”, only to believe that this was all in the professor’s head? Sometimes they just get it entirely wrong. Consider Rolling Stone’s initial response to Led Zeppelin, arguably the most popular rock band of the 70s: “Jimmy Page is…a very limited producer and a writer of weak, unimaginative songs, and the Zeppelin album suffers from his having both produced it and written most of it”. The Zep could take solace in knowing that at least they were worth the trouble of reviewing. Who wouldn’t sacrifice limbs for a bad review in Rolling Stone? To be insulted on the national stage, now that would be something to write home about. Fueling critical misunderstandings was the fact that Walls Of Genius was a little different than most of the groups or individuals pursuing the “cassette culture” of the 1980s. While some were rock-music oriented, the vast majority of the scene was about performance art, noise music, sound-collage, industrial, ambient drone and other aspects of experimental and non-commercial music. As has been pointed out to me, some local cohorts saw Walls Of Genius as nothing more than old folkies who dared dabble with experimentation, attempting to worm our way into their world. Walls Of Genius pursued all these genres in the course of our career, but first-and-foremost, I think WoG could be characterized as being a rock-band at the core. But we were also an experimental performance-art improvisatory comedy ensemble. We never shied away from pursuing sound collage, industrial, noise music or even musique concrète. By running the gamut like that, we also ran the risk of being reviewed by individuals who didn’t understand or appreciate our pan cultural perspective. If what you expected was industrial noise and you got the Fabulous Pus Tones instead, you might not “get it”, even though the philosophical intent of cultural deconstruction originated in the same impulse. Thus we found ourselves presenting the Fabulous Pus Tones at Denver’s “Festival Of Pain”, a primarily industrial noise-music event. The discussion of what constitutes “rock music” and “rock bands” is a dissertation for another day. The point here is that the cassette culture didn’t always know what to make of a Walls Of Genius album. Both that “confusion” as well as clear- eyed assessment led to many different kinds of reviews and a few that were far more critical than celebratory. And, of course, it was a public arena. No point in getting pouty about it. Nixon and Barnum notwithstanding, there’s no such thing as bad publicity. Towards the early days, the punk-rockers at Warning Magazine (Anchorage AK) warmed up to our cassette “Sunday Monday Or Always”, despite the fact that it wasn’t “hardcore at all”. Own The Whole World called it a “bent and twisted smorgasbord, just my cup of tea.” Objekt described our album Sunday, Monday, Or Always as “demented damage that brings new meaning to the word ‘annoying’.” Robin James in the “T” issue of Op gave The Many Faces Of Mr. Morocco a mixed review, alternating between having his socks knocked off by my recitation “Bugs”, but notes that the remainder of the music wasn’t as good. The Fortnightly College Radio Report called Walls Of Genius “Bar Mitzvah music for Martians”. We ate it all up quite willingly. The reviews encouraged us to think that our activity possessed value in the underground marketplace. Turned down by Ralph Records, we got a nice letter from them indicating “we do our best but it often is not enough, nice try guys”. Attempting to garner distribution from Wayside Music, we got a grumpy note indicating “not the sort of thing that I am personally fond of.” Turned down, again, by Rough Trade Records, we got a nice note saying “found to be quite entrancing…(but) more suited to a literary audience”. Well, perhaps not entrancing enough for a record contract. After a while, the reviews grew consistently positive as the community of reviewers became accustomed to the onslaught of titles from Walls Of Genius. By the time of Before…And After, we received copious praise. Turning the corner was the follow up, a self-consciously sophomoric ode to desire, The Mysterious Case Of Pussy Lust. It didn’t really matter at that point whether reviews were good or bad because it was the publicity that counted. The fact that it was even worth discussion was the main thing even if we disagreed with the assessment (‘Zappa wannabes’). We can all get pouty sometimes receiving criticism where we had hoped for praise. Especially vicious criticism can be quite disarming and disillusioning. I once lashed out at an old friend because I thought his new music was ridiculously pompous, aggressively self-indulgent and too self-consciously smart for its own good. In retrospect, I regretted my response. After all, he had long been on a self-ordained mission as a prog-rocker and, in the process, had once taught me an awful lot about how to play the bass guitar. When it came time many years later to pen a critical response to a manuscript written by yet another talented friend, I made every effort to be as gentle as possible. The crux of the critique was how to make a villainous character believable to me as a reader. Nevertheless, that response ended the conversation and that particular novel was never mentioned again. What was the psychological reaction to such critical responses? Did my friends think I was a high-handed git? Maybe I was, but we’re all still friends. Music criticism is not the monopoly of the reviewer. Musicians themselves can be as cruel as six-graders on recess. Note George Harrison’s petulant comments to McCartney in the Let It Be film. How many times at band practice has somebody stopped in the middle of a song and cried out, “you’re speeding it up… your phrasing is wrong… you’re singing the wrong harmony… that’s not how it goes…No no no!” I have always taken an experimental approach to see what works and what doesn’t. When it comes to others’ parts in a band, I’m willing to provide direction at times, but mostly I’m in favor of letting each musician figure out his or her own proper role in the song, to discover that role via an organic process and to correct their own errors before having them pointed out. Nobody likes to have their errors pointed out, especially if they’re in the process of correcting them by experimentation already. Not all musicians see it this way. Even worse is when the criticism comes during performance. With an audience before us, an acquaintance once tried to educate me about what he thought the correct chords should be in the song I had just played, “Sunny Side Of The Street”. It was my stage at the moment, I was the primary performer and he was helping along with bass-lines on the side. I was livid: “You don’t correct a performer in front of an audience!” I never played with that acquaintance again and we’re clearly not friends anymore. I thought that on-stage intervention was about the rudest thing ever. Until we took a break. After my short set on acoustic guitar, I had moved over to the bass, playing with a chops-heavy drummer and his keyboard protégé. During the break, I overhead the drummer tell the keyboard player, “There’s just no good bass players on the Front Range”. Hey, I’m playing the bass tonight and I’m standing right next to you, Ass-hole! How is that supposed to make somebody feel? Maybe my jazz chops weren’t up to his standard, but at least I was trying. Was there anything he could do to improve my confidence, to help me play better? No. In fact, he was determined to go so far as to discover and uncover my limitations, as if it was a “cutting contest”. That’s no fun unless you’re a virtuoso and who wants to play with musicians who aren’t any fun? A third story I’d like to tell here is about the legendary Walls Of Genius show at Pearl Street Music Hall in Denver with the group “Fish Music”. We had invited a bunch of friends, thinking we would be opening for Fish Music, but arriving at the venue, we were informed that we would go on afterwards. Which meant an unexpected midnight start-time. By the time we got on stage, after what proved to be an interminable extended set by a C-grade noise band, we only had a few stalwarts left in the audience. Jimi West of Denver punks Rok-Tots called out for “Magic Carpet Ride!” So I launched into my arrangement, which had been on one of our cassettes. It was nothing that we had ever practiced. Ed stopped playing and said, “that’s not how it goes…” What do you mean, that’s not how it goes? It’s my arrangement! It was on the cassette album! Play through, my man! But Ed wasn’t on that recording and he didn’t know the arrangement and he lacked sufficient imagination to roll with those punches. Since we had stopped in mid phrase, I hit the opening of “Born To Be Wild” and we played that instead. I hate being corrected on stage! Who wouldn’t? And what about “constructive criticism”? As far as I’m concerned, that’s an oxymoron, nothing but a euphemism for “if you don’t change your ways, you’re fired”. One of the philosophical problems of criticism is that the critic gets to criticize, but the victim seldom gets a venue to critique back. Typically, the “boss” gets to criticize you, but you don’t get to criticize the boss. So it’s a one-way street at the workplace. With music, it’s a little different. There is no expectation of critiquing the critic. Sometimes you’ll get ‘constructive criticism’ that helps develop a piece, from both critics and fellow musicians, but most of the time you don’t want to hear it. The challenge is to issue that criticism in a positive manner, unlike the the time I unloaded on my prog-rock friend back in the 80s and, having learned my lesson (I hope), why I tried to be so gentle with my novel-writing friend in the 90s. Criticism…can’t live with it, can’t live without it. In the long run, without it in the form of reviews, how is anybody to know what they might want to give a listen? At the very least, when you read those reviews, both negative and positive, in the underground press, they gave you an idea of what you might like to try next on your stereo. There were very few radio stations playing the underground music back in the 80s and most of that was between the hours of midnight and dawn. In the 21st Century, the problem is just the opposite—more hours of on-line radio than any one listener can accommodate. The cassette culture of the 80s somehow found just the right balance and the critical reviews were a big part of it.

11 Comments

|

Archives

January 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed