|

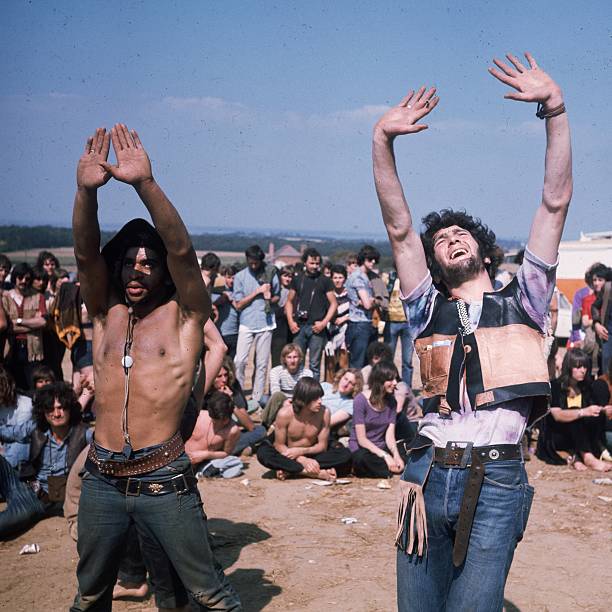

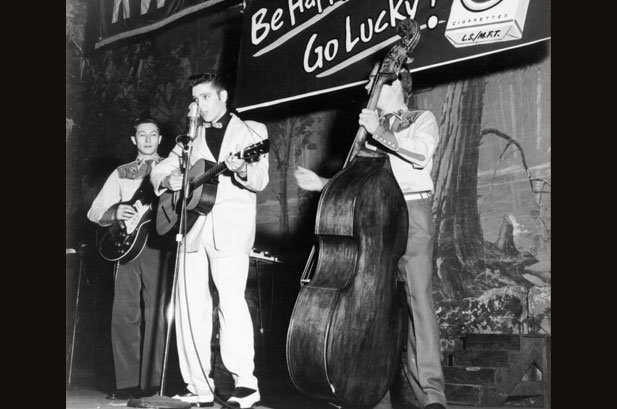

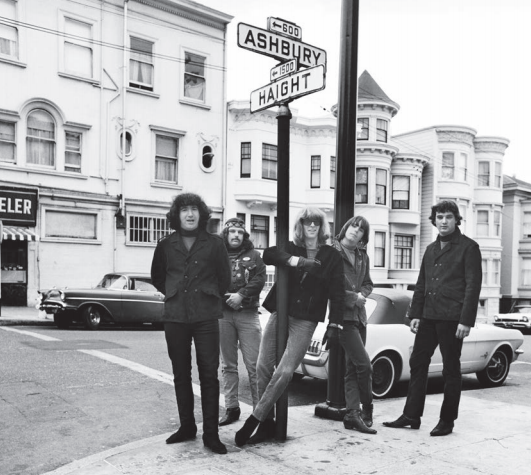

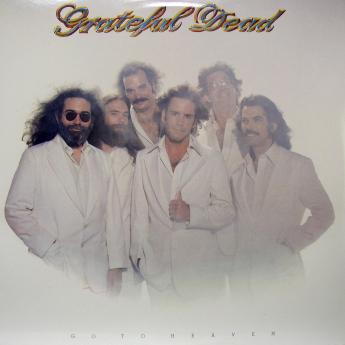

Why Don’t I Listen to New Music? by Evan Cantor Why don’t I listen to new music? It’s not like I don’t hear it. I hear it all the time, on television, in movies, out-and-about, at friends’ houses. And I must admit, a lot of it sounds damn good. But am I really listening to what I hear or is it just “Muzak” to my ears? Even when I hear a new song that I like, I don’t have the same enthusiastic responses I exhibited in earlier phases of my life. The last time I remember hearing music in a public place that piqued my interest and caused me to prick up my ears was many years ago. When I asked, for the third time, “who was that?”, it turned out to be Nirvana. I’m not talking about the variety of underground sounds that you might hear via Electronic Cottage. I’m talking about the mainstream music culture, which all of us over a certain age happily grew up with in the 1960s and 70s, a culture that, to a certain extent, still exists today. So, for me, questions remain. Was it a golden age of pop music? Is my generation (the baby-boomers) prejudiced, self-absorbed and self-important? Is it a psychiatric phenomenon? Does today’s music really suck? Is celebrity culture out of control? I’m not surprised that my lack of interest in new music may be related to all of these things. Let’s start with psychology, as it seems to reflect my own experience most accurately. Some research studies indicate that people develop individual tastes in their youth and carry them through the rest of their lives. So the crowd that jitterbugged to Glenn Miller may have objected to Elvis, Sinatra fans certainly recoiled at the Beatles and hippies dissed Disco while twirling to the Grateful Dead. Certainly adolescence is an important time in developing one’s character. Neurological research indicates that while the emotional centers in the brain are well-developed by adolescence, the rational centers are not. Reason matures in the brain around age 30, which accounts for the extreme behavior of teenagers, from bullying and heart-break to suicide. So when it comes to music culture, the adolescent is absorbing all kinds of wonderful new things in a highly emotionally charged state, as is the young adult, having no real experience or attachment to the past. There is a kind of imprinting upon the brain that has consequences for the remainder of a life. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Psychology_of_music_preference University of Rochester Medical Center Perhaps at some point in such a life, one has heard all the new music one’s brain can possibly absorb and a mental ‘canon’ is established (as opposed to a ‘mental cannon’). At this point, new music presented to the brain is absorbed via a postmodern relativistic process. The brain attempts to categorize something into areas with which the listener is already familiar and understands. While this idea reflects my own experience and may be the case for many, it is certainly not the case all across the board. I know a lot of folks my age (60+) who are, like me, focused and obsessed with the music of their past, and by extension our own youth, but I also know an equal number who quite enthusiastically listen to new music. As a concept, however, rejection of new things has historical precedents. For instance, Mahler was rejected by fin de siècle (19th century) Vienna. Shakespeare was not considered “classic” until well after his own time. How about the Impressionist painters? A lot of new stuff goes unappreciated by the establishment. Which is one of the reasons so many of us were motivated by Rock music in the 60s. It pisses off the parents? Good! I’m not a parent, but a lot of my friends are and I can attest that we’re not all entirely happy about the music our children embrace in 2018. As Brett Kavanaugh so toxically reminded us, ‘what goes around, comes around’. He may as well have said ‘the more things change, the more they stay the same’. Today’s kids have found musical forms to which ‘we’, the geezers, now object. If my parents’ generation found 60s pop music to be excessively and overtly sexual, how would they respond to today’s hip-hop? As an adolescent, I thought the sexualized world of the 60s was exciting. I was myself awash with hormones and desired that action myself. But really, did I know what Eric Carmen was singing about when he asked us to “go all the way”? No—primarily it was the sound of the music that I liked. Who knew what Mick Jagger was singing about as he drawled his way through all kinds of salacious material. “Brown Sugar” was about sex with slaves? It took me years before I got that. Thanks to developments in recording technology, lyrics can be understood quite clearly, if so desired, in 2018. As sex is timeless, “Let’s Do It” has become “Let’s Fuck”. I might not like it or think it particularly elegant or romantic, but I didn’t grow up in this culture, so I can’t condemn it out of hand. Joe S. Harrington in his book “Sonic Cool: The Life And Death Of Rock’n’Roll” puts forth a corollary to these notions. His primary thesis is that “Rock’n’Roll” is defined by its opposition to mainstream culture. Thus, Elvis was rock’n’roll in his early days, as he experimented and discovered a way to bring the enthusiasm of black rhythm’n’blues to the white audience (if indeed that was his intention). But when he became uber-popular and over-produced, he was no longer rock’n’roll because he had become the mainstream at that point. Sold out, so to speak. So it has been with various movements in fin de siècle 20th century music. Psychedelia, prog-rock, heavy metal, disco, punk, grunge, hip-hop: all of it has become mainstream. New genres have not appeared, only post-modern mash-ups of various classical influences. Harrington is talking primarily of the music of my youth, so not only did I develop my taste as an adolescent, my youth was awash with the exciting developments of these genres. As a boy, I fondly recall my parents’ Dixieland jazz and bombastic classical records, but it was 60s rock’n’roll that brought me to the table. I was too young to be energized by the emerging Elvis or to sneak into blacks-only clubs to hear Louis Jordan’s jump blues. But the Beatles surely energized my formative years. The developments of popular music in the 60s was in itself a precursor to postmodernism, as it led many of us, myself included, to the exploration of our generation’s musical predecessors. We dug deep in cut-out bins for blues, rockabilly, rhythm’n’blues, jazz, country and bluegrass. We listened to Cab Calloway invoking us to “rock”, Louis Jordan declaim that “they were rockin’” and Hank Williams urging us to “rock it on over”. Improvisatory psychedelic music led my generation to explore experimental areas, like John Cage and Arnold Schoenberg, Philip Glass and Terry Riley. Our tastes developed on parallel lines as popular music itself grew and evolved. But was all this music really better than the music being made now, in 2018? Probably not, but it did come first. Because of its priority in the linear time-line, “classic” defines the genres. Whether or not today’s music is the equal of its classic predecessors, it cannot help but be postmodern by definition. Thus, the entire twentieth century remains a golden age not just of rock music but of modern music altogether. So, no, today’s music, postmodern as it is, doesn’t (probably) actually suck. I know full well that there are countless contemporary proponents of all these styles doing tremendous work. But back to contemporary pop music. A lot of it certainly does seem manufactured in a revolting, overwrought, over-produced and over-the-top manner. Why do I take little notice of the Beyoncé phenomenon when I was more than happy to ingest manufactured music from Motown, Stax and the Wrecking Crew back in the 60s and 70s? Weren’t the Monkees a manufactured product, created to fill a niche in the market, an American faux-Beatles a-la-Hard Day’s Night? Of course they were, so the question remains why over-production and commercialization are sometimes obnoxious and sometimes not. We all seek authenticity in our lives and perhaps that is the difference between well and over-produced music. David Byrne, in his book “How Music Works”, asks us why good production is viewed as ‘inauthentic’. In terms of sincerity or authenticity, production shouldn’t make any difference at all. For instance, I like Willie Nelson’s songs, but I find most of his ‘classic’ period to be obnoxiously produced. Willie doesn’t need to be slick. Does he really need a string section? When the Grateful Dead finally got smooth crystalline production, I thought the soul had been sucked out of their music, the authenticity lost. We all accept some commercial entities, but not others. The Beatles were transformed from leather-jacket rockers into a commercial juggernaut complete with matching suits and blow-dried haircuts. Why was this not objectionable? Perhaps it was. How many die-hard Liverpudlians happily accepted their local boys selling out and going global? And why do I react so poorly to the parade of clearly manufactured divas and manically rhyming rappers on Saturday Night Live? For starters, I appreciate what I perceive as a good song. I’m not disgusted when I hear a good song. I can groove to Lady Gaga, even if I’m not paying much attention to her. And yes, I’m the judge, jury and executioner of my own taste. What constitutes a good song? That’s a dissertation for another time. Another element of authenticity, or the idea of it, is “soul”. Are Beyoncé’s entertainment spectaculars bereft of soul? If so, how did the Monkees obtain it? Henry Miller once wrote “Everything has soul, including minerals, plants, lakes, mountains, rocks...everything is sentient…” (Tropic Of Capricorn) And I agree with him. So Beyoncé is not a soul-less automaton and her creations must have some kind of spirit or soul. They clearly appeal to a great number of people. Am I an elitist snob who sees my own taste as morally superior to that of others? I’d like to think that’s not the case. In many ways, James Brown’s spectacular performances in the 60s were no less choreographed and manufactured than Miss B’s, but I love those recordings and don’t doubt the amount of soul injected into them. So, is my rejection of new music and lack of attention caused by disgust with a celebrity culture that has spun far out of control? This is a distinct possibility, but it should be noted that celebrity culture is not a new phenomenon. Mass media has simply made it more global and ubiquitous in nature. Charles Dickens and Lord Byron were both hounded by 19 th century paparazzi and caused female fans to swoon at readings. I was as fascinated by Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix and Jim Morrison as any other 60s rock listener. I don’t resent Elvis’ celebrity, just as I don’t object to Benny Goodman’s, Django Reinhardt’s or Glenn Miller’s from a previous era. But as our economy (at least in the USA) grows ever more dependent on consumption as opposed to creation and production, our worship of celebrity seems to have grown into a collective neurosis. Such a collective neurosis as celebrity worship may only be a natural phenomenon in human cultures. After all, we have always sought leaders, heroes, martyrs and saints. In the 20th century, mass media brought these heroes right into our homes, moving before our eyes on television, speaking to us over the radio, their photographs plastered in magazines and newspapers. We only had so many newspapers and so many television and radio stations. The early age of mass media was, in many ways, despite specific demographics left out, a collective culture. What was once collective has devolved into parts, no longer unified by common experience. Modern tribalism runs the gamut from right-wing Aryan-nation freaks to pinko libtard snowflakes. Celebrities play right into this, perpetuating the tribal identifications, political, artistic and athletic. I know that celebrities are people who put their pants on one leg at a time like the rest of us. One can admire a person’s work without indulging in hero obsession. So it might be that my disinterest in new music has something to do with rejection of celebrity culture. I wouldn’t rule it out. It is wise to remember, too, that sometimes you’re better off not to meet your heroes. My interest in music started, at least consciously, with Dixieland Jazz in my parents’ record cabinet. Along came the Beatles and the discovery, via short- wave radio, stations out of Detroit playing the music that the Beatles had emulated. I embraced the American Top-40, subscribed to Billboard Magazine, and fell in love with the rock music of the sixties. It was certainly postmodern in the sense that pop musicians were re-visiting earlier sounds such as jug bands and the blues. That world of popular music kept growing, year-after-year, from the British Invasion to Prog-Rock, Heavy Metal and the psychedelic San Francisco Sound. Punk and Disco came along. I embraced Punk, but Disco? That was my first rejection. I was a ‘Disco sucks’ post-hippie punk. But there was more coming. I liked New-Wave, ska and reggae and found myself interested in Grunge when that came rolling by. I had never liked Hardcore Punk and while getting into the avant-garde missed the era of Big Hair Rock altogether. In retrospect, Disco sounds pretty damn good to me. Hair Rock just sounds silly, although I’ve turned up some good songs whose production was clearly over-the-top. Heavy Metal has long been excessively overwrought for my taste (think too much operatic scream-singing) and I hardly listen to any punk rock at all despite being a 70s enthusiast. Not that I’m listening to a lot of Disco, but it’s out there and I hear it, here-there-and-everywhere. I hum along and tap my foot. I’ve even jumped up onto my desk at the workplace and danced to it. Why did I dislike it then, but accept it now? Perhaps I’ve come full circle with the psychiatry. I can’t help but like it. For good or for bad, it was part of the music of my generation and I no longer think about it as something divorced from the music I liked best at the time. It was all wrapped up together in the package that was my youth. But still, that doesn’t explain it entirely. Witness my response to Hair Rock and Heavy Metal. I recently read Eric Von Schmidt’s “Baby Let Me Follow You Down”, about the folk music scene in the late 1950s and early 60s, a scene that went far in creating the foundations of the folk-rock I loved so much in the 60s. I did some poking around on Youtube. Bob Dylan had infamously “stolen” Dave Van Ronk’s arrangement of “House Of The Rising Sun”, so I googled Ronk’s version, which I found to be slow, drawn-out and lachrymose. There’s no way he was going to generate excitement outside of a devoted folk scene, no matter what he thought of Dylan. I listened to Von Schmidt, a ‘revered’ figure of the scene, known for his blues renditions and was equally unimpressed. Carolyn Hester found herself a bit useless as she was eclipsed by Joan Baez. After having given tips and taught songs to Joanie, she had become just another ‘Baez imitator’. I listened to her as well. Not bad, but not electrifying in the Baez sense. The microphone hears nearly everything, except maybe the vibration of the live performance experience. But recordings of Howlin’ Wolf in those same years sparkle with excitement. So I’m clearly not equally enthused about everything from my generation’s musical past. I am, however, strangely enthused about Disco retroactively. I like funk and Disco fits the mold. But I exhibit little or no enthusiasm for some other contemporaries of the time. As a teenager, I loved what passed for heavy metal: Alice Cooper, Deep Purple, Steppenwolf, Led Zeppelin. I dabbled in Black Sabbath, but never really got into it. Those groups were arguably far less bombastic than later versions of the form, whose players were clearly virtuosic and exciting, but whose music failed to move me nonetheless. Another contemporary to whom I never warmed was Bruce Springsteen. He’s hugely popular, I acknowledge his songwriting prowess and realize that he is friends with personal heroes like Patti Smith, but still… The first I ever heard of Springsteen was when, after a Grateful Dead concert, I was hitch-hiking from Richmond to Charlottesville, Virginia, and the people who gave me a ride were singing his praises. I heard his music and went “feh”. Thirty years later, a co-worker attempted to convert me to the church of Bruce and I bought a couple of the man’s albums. They’re not bad, but they continued in failing to grab me at an emotional or visceral level. This is part and parcel of just how ineffable our tastes can be. Why do some people love ice-cream sundaes but others want chocolate cake? Bourbon or Scotch? IPAs or Belgian Saison? The answer must lie somewhere below the level of consciousness, a place that is damnably difficult to explore and understand. Of course I had my own tastes and I was never afraid to exhibit them at high volume. In my first-year dorm at University of Virginia, I got embroiled in a stereo war with a fellow resident. He played the Beach Boys endlessly at maximum volume and I thought the Beach Boys’ music was overly-white-bread, bland insipid bubble-gum. I knew better than to listen to that crap. I listened to bracing, intellectual stuff like Blue Oyster Cult, Yes and Tchaikovsky. So I blared my stereo, too. In retrospect, damn don’t the Beach Boys sound good. So do Blue Oyster Cult, Yes and Tchaikovsky, for that matter. Which brings me full circle once again to having grown up in some kind of a Golden Age of Music, witness to some of the most fabulous developments in pop music ever. Maybe today’s music will be remembered that way sometime in the future, but I’m not holding my breath. The bottom line emerges for me despite a novel’s worth of intellectual palpitations. No matter how I parse the matter, I actually do believe that today’s

popular music sucks. Sure, there was something magical about growing up with the developments of fin de siècle 20th century popular music, getting a year older with every birthday and waiting for the new Beatles album to point the way for another year of pop music. I’m grateful for that experience and I loved the music. Teenagers in 2018 may or may not be growing up with comparable sociological developments in trip-hop, Nashville pop, house music or whatever. As I find this music of little interest, I can’t begin to follow its developments, but I suspect it’s not the same. I’m glad that the wonders of recording technology have made the past available to be explored. If the samplings of today lead people back to a glorious musical past, then no doubt the classic music will live on. What would my generation have thought if there were actual recordings of Mozart playing the piano, improvising endlessly on compositional elements that we could only know from the static page of sheet music? We’ll never know, but when it comes to the 20th century, the recordings are there for all to hear and we’re still listening. I can honestly accept that enthusiasts of today’s music may dismiss me as a cranky geezer. It’s my gut feeling that the recordings will continue to justify my opinion. And opinion is all it really is.

20 Comments

|

Archives

January 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed