|

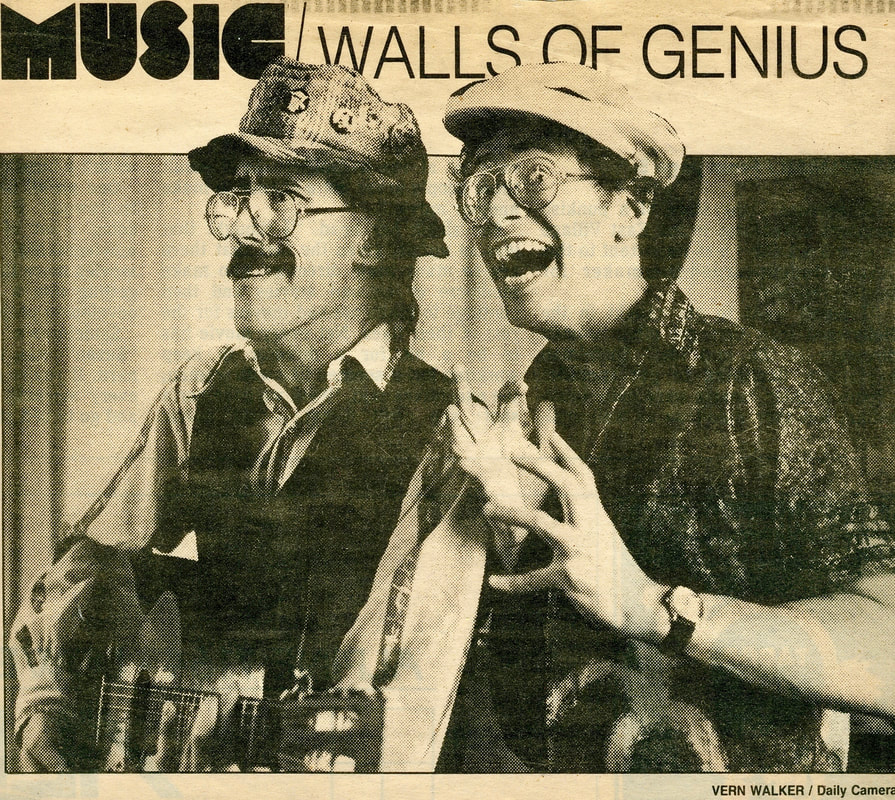

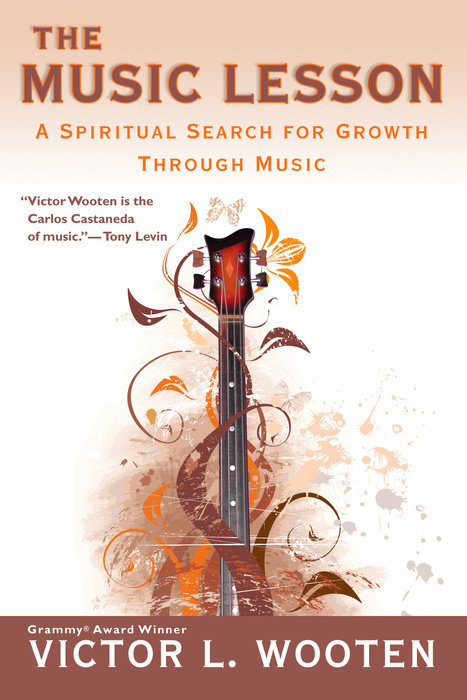

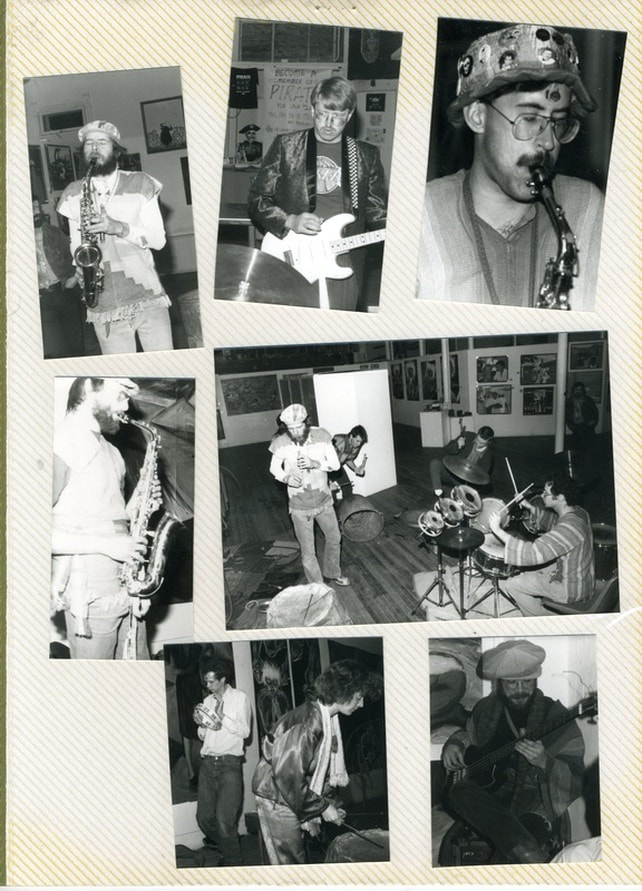

A lot of what we did in Walls of Genius was improvised, either partly or in full, essentially creating something out of thin air much of the time. Sometimes it was live on stage, other times right in the so-called studio. Even when we were doing “songs”, we would often launch into lengthy improvisations related to the song structures only by virtue of (usually) staying in the same key. How is this done and can anybody do it? Well, it’s not necessarily easy to explain and as for the second question, it’s sort of yes-and-no. I’ve known many musicians who are uncomfortable with improvisation, especially where no previous song structure exists. They apparently require (or prefer) a structure to support the whole, as opposed to creating that structure on the fly. For the structural approach, think Miles Davis’ cool-jazz period, where the band improvised on extended song structures. For the unstructured, start-from-scratch approach, consider his electric years when he quite often showed up in the studio with two chords written on a paper bag and set the musicians on ‘play’. There’s nothing better or worse with either approach and at Walls of Genius we pursued both quite gleefully. Note the example below, a live version of the Alice Cooper song “I’m Eighteen”. The improvisatory section, while remaining in key, takes off from the song structure into a crazed chant. It’s nice to know the structure of a song and have the chops to play it, but I’m not talking about live jukeboxes churning out note-for-note covers for wedding receptions. If you’ve got the chops and discipline to do that, more power to you, but I know that I would find it boring. The only way I can understand how a musician could possibly enjoy playing in a “tribute band”, churning out note-for-note covers of somebody else’s music, is to liken it to classical music. The classical musician, in an orchestra or string quartet, is playing the music verbatim from sheet music, note-for-note. That’s a tough nut for me. I like putting my own spin on things. In fact, it’s hard for me not to put my own spin on things. It’s always fun to learn a song correctly and it’s even more fun to do it “my way”. Improvisation lets you go further. That’s where you get a chance to go exploring. Starting your adventure from scratch, however, you will find something magical and different in the creation of something out of nothing. A note here, a note there, some rhythm added and a new piece is spontaneously created. If it’s “on tape” (or was the result of particular combinations of riffs in the first place) it can be re-created. But if not, even if it’s a complete and total “one-off”, there it is, on tape, recorded for posterity. Listen to Hal McGee’s collages of daily life—they are all improvised one-offs, not designed to be re-created. With my improvisatory band, Strange New Worlds, we took it to the far limit, never playing the same thing twice. We would set up and compose from scratch every time we played, whether in the studio or on the stage. We didn’t even discuss what we were aiming for or where we wanted to go with it. Our only plan was to start messing around until something jelled and it almost always did. Without recording technology to capture those bursts of creativity, it would be lost for all time. If we were playing the Burning Man Festival, that might be the point, but we weren’t. Bassist Victor Wooten, in his book “The Music Lesson: A Spiritual Search For Growth Through Music”, articulates so much of what I already believed about improvisation that I would recommend it to anybody who loves making or listening to music. It might be a little airy-fairy for some readers when it comes to his spiritual pronouncements, but there’s a great deal of truth in it, especially for those wishing to pursue improvisation. The italicized passages below are culled from Wooten’s book and provide points of departure for my own reflections. “Music is real, female, and you can have a relationship with her…like one-hand clapping, a one-sided relationship never works.” Of course music is real. We’ve all heard it, so we know that it exists. “Music” (with a capital M), however, is a spiritual concept, a continuum and a channeling of energy. This is not something that can necessarily be measured, but is manifested quite clearly when we say a band or a player is “on” or “hot”. The channeled energy flows like a river through the artist into the audience and back. If the energy (a/k/a “xi” or “chi”) isn’t flowing, the musicians are either incompetent or having an off-night. I couldn’t say whether or not “Music” is female, but I agree that you must have a relationship with it conceptually in order to make it work as effectively as possible. It is a kind of magic, like karma. You only have to put a little bit into it to get a lot back. How do we know this energy exists? Well, we don’t, not really. It’s a metaphysical explanation for a common experience that cannot be fully quantified scientifically. It could simply be the stimulation of adrenaline, endorphins and serotonin. But does it matter? Either way, it’s a physical and mental state sought by both musician and audience. When musicians feel like a “bird in a flock”, a sensation created while a band is “on”, that is not a measurable phenomenon. You could score a band on whether or not they were having a good night or were sluggish, but how would you go about it? What would it mean to grade a band on a scale of 1-to-10, with ten being the best concert ever? Would that score be meaningful? “Guys, we need to up our game, we were only about a 7 tonight…” If anybody told me that, my first instinct would be to tell them it wasn’t my fault and could you just fuck off? But this phenomenon can be experienced. “You should never lose the groove in order to find a note…Once you find the groove, it doesn’t matter what note comes out; it will feel right…You are never more than a half-step away from a ‘right’ note.” I learned this lesson playing the fretless bass. When I worried about hitting the right note at the exact spot on the neck, I couldn’t do it. But when I gave up worrying and just let the groove happen, it didn’t matter if I hit the exact “right” note or not, it sounded just fine. The groove was more important. One of the magic tricks in improvisation is that a “wrong note” is often just an opportunity to go in a new direction. If your music is sufficiently experimental or avant-garde, notes might even be superfluous. Noises or abstract sounds might suffice. What does it mean to only be a half-step away from the ‘right’ note? Well, you can always slide a note up or down to arrive at the so-called correct note. Your audience will think you intended to play it that way. There are other tricks as well. For instance, if you look at the shape of chords on a guitar neck, you may notice that a Bb6-barre shares many of the same notes as a G-minor-7th. If you only play the four highest notes in the chord (strings 1-2-3-4), those chords are identical. One benefit of looking for these kinds of cross-overs is that you can give your fingers a break by abbreviating the chord. Another benefit is that you can make the music richer harmonically. Maybe a Bb6 will fit in that place where the sheet calls for a G-minor-7th . “Repeating the ‘wrong’ note allows the listener to know where it’s going so that it begins to sound ‘right’… it’s a great way to correct mistakes after they’ve already been made… We can’t avoid making mistakes, but we can get comfortable with them.” When you’re performing, you must never stop playing simply because you made a mistake. You have no choice but to play on through and most listeners won’t even notice, especially if you’re comfortable doing so and don’t make an awful face. In an improvisatory context, you may be able to turn the mistake into a fabulous new musical journey. I can’t tell you how many times this happened with Walls of Genius. Artists call these mistakes “happy accidents”. In a song context, if you just keep going, nobody will know you even made a mistake in the first place. Of course, if you are recording, the microphone will hear the error and you will very likely want to correct it in some manner. But when you are practicing or playing live, keep going so that you learn what it feels like to play through a mistake. What happens when you stop in the middle of a song? The energy flow shuts off and you lose both your groove and audience. This once happened to a friend of mine. He had wangled his way into a fabulous venue opening for a famous name act. It could have been a tremendous opportunity for him. Halfway through one of his songs, he stopped and explained that he was recording the concert, had made a mistake and was going to start the song over again. The audience very likely hadn’t noticed anything because they had never heard his songs previously. He didn’t really need to have every song recorded perfectly. So what if one wasn’t perfect? I never heard that recording and he never got that gig again, losing multiple potential connections in the process. God rest his soul, Bob was a tragic victim of his own demons. “A true musician plays Music and uses particular instruments as tools to do so.” Making music does not depend on what instrument you play. Music is not about technique or virtuosity (although that can certainly be an interesting part of it). It is about the larger concept, “Music” the spiritual continuum. As far as my chops are concerned, I am a strong vocalist and can play (well) rhythm guitar, blues harp and the electric bass guitar. I can play lead guitar if I have enough distortion and you don’t mind a kind of crazed punk approach. I can play (middling) the baroque recorder, keyboards, upright bass and percussion. I have played numerous other instruments as well, regardless of how poorly. Put it in front of me and I’ll give it a try. Sometimes only one or two notes is all you need. When I played the saxophone with Leo Goya’s group The Miracle, I didn’t know squat about playing the sax, but I could apply what I knew about “Music” and thus contribute to the free-jazz chaos. When it comes to my vuvuzela (in the colors of the Mexican soccer team), I can make one note. Granted, it’s a loud note and it sounds like a dying hippo. I have not yet used it in a recording… With Walls of Genius, we would try any instrument at hand. Frank Zygmunt once pulled an old warped autoharp from a dumpster and gave it to us. Both Little Fyodor and I managed to make very interesting and spooky music with it. Not that either of us “knew” how to “play” it or bothered to tune the warped old piece-of-crap autoharp. Frank also gave us a big sheet of plastic, very likely a lens for a fluorescent light fixture. We would wave the thing around and make a wonderful “woop woop” sound with it. It wasn’t even a musical instrument in the first place. A lot of the earliest incarnations of WoG were made with children’s toy instruments in Ed Fowler’s apartment. More recently, Ed came to a WoG session with three ukuleles. I thought he must have been practicing the uke, but no, he said that I would have to play them! I had never played the ukulele before. So I looked at his ukulele song book, practiced a few chords. In minutes we were off and running with “All My Loving”. Does that mean that I am one of Wooten’s “true musicians”? Maybe. I’d like to think so. “The bass guitar… is understated and underappreciated, yet it plays the most important role. The bass is the link between harmony and rhythm. It is the foundation of a band. It is what all the other instruments stand upon, but it is rarely recognized as that.” As a bassist myself, I have always known that I was doing more than just holding down the time signature. The bass is continuously laying down a foundation for the harmony and melody, not to mention taking single-note leads since it rarely plays anything resembling a multi-note chord. I suppose it can be overdone, though. When I saw Mr. Wooten in concert, outside his progressive bluegrass context and doing his lead-bass thang, it was a bit over the top. Some restraint and good songs wouldn’t have hurt him. It certainly wouldn’t have hurt him to have taken his own advice. But yeah, I concede the fact that he had the fancy gig and adoring fans, so whatever he was doing must have been right for him. “Imagine if we allowed beginners to jam with professionals on a daily basis. Do you think it would take them twenty years to get good? Absolutely not! It wouldn’t even take them ten. They would be great by the time they were musically four or five years old. Instead, we keep the beginners in the beginning level…There are professionals you can bring here to you… (on CD)” Playing with others is always a learning experience. Wooten asserts that letting beginners play with accomplished players would heighten the learning experience and I agree with him. But this is not always possible and, in many cases, not even desirable, especially to those accomplished players. I use the skiing analogy—if you can whiz down the double-black-diamonds, you’re going to get bored really fast out on the green runs with the novice. A run or two, maybe, but more? Probably not. But beginners, don’t despair. You can use your stereo or computer and play along with anybody you wish. It’s not the same as playing live with better players, but it’s fun and is always a learning experience. With YouTube, you can even see (some of the times) how a musician is playing certain parts. This is why Django Reinhardt was famously nervous about being photographed while he performed. He didn’t want people to see how he did his thing. Nowadays, you can learn, from one source or another, how to play almost anything. But chops are not soul. Learning how to play well with others is the real trick in improvising, both live and/or in the studio. When you’re playing with others, you need to scale back and play less. The more players in the room, the fewer notes each player needs in order to fill the room with music. Five players, all restraining themselves, can create an incredible sound together. Without restraint, the result will usually be cacophony, which is, admittedly, sometimes a desired end. But not always. Most of the time, the players around you will appreciate it if you restrain yourself. I eventually gave up playing with The Miracle because I felt too many players were involved. When we lost George Stone’s jazz piano as a touchstone and lined up as many as six saxophone honkers all in a row, it had morphed from music into cacophony. This didn’t stop Little Fyodor, though, and he kept The Miracle alive through many more sessions, many of which produced credible free jazz and avant-garde music. What if you’re handed a recording that was itself an improvisation and asked to overdub additional parts? I approach this by improvising with the improvisation. I know I’ve found the parts that fit when they sound like they were improvised in the room alongside the original improvisation. The excerpt below began as a percussion track. Inventing a part on the spot, I added bass and then finished up with electric guitar. “The way you play notes causes them to sound different… changing the duration allows your ear to hear and respond differently…” There’s a real difference between playing legato (slow), staccato (pointy) or allegro (fast), for instance. Or cutting a note off abruptly versus letting it ring. Think about the endings of songs, for instance. Even after long improvs, a good solid ending is better than a fadeout. It makes your group sound “tight”, “competent” and “together”, even if the improvisation is itself sloppy. Witness the success of numerous jam bands. Whether you stop a note abruptly or let that note ring makes a difference, but only you can tell which is best in the situation. If you pound on your keyboard, it sounds different than if you tickle the keys. If you finger-pick a G-chord on the guitar, it sounds different than wailing away on the same chord with a heavy plectrum (pick). “Most people play louder to get someone’s attention, but getting quieter can stop a bull from charging… Most artists think the louder they play, the more emotion there is. Actually, it is the other way around. The emotion has to be real when you are not hiding behind loud volume.” Dear Lord, Yes! Most musicians let volume get out of control. Rather than get louder in your effort to communicate your message, take it down and explore the subtle mysteries of minimalism. Can you say more with less? If not, you are limiting yourself as a musician and making it more difficult for other musicians to play with you. “I could tell that the drummer had chops, but the fact that he wasn’t showing them off was impressive…If you don’t play the rests (and) give them the same attention that you give the notes, you’ll rush.” Drummers are notorious for volume, but they’re not the only musicians who chronically overplay. Think of those players who must exhibit every note, every lick or run that they have ever learned, and play them all at once. They think that they must impress the hell out of you (or, in some instances, make you go away). They take up too much space. They are not necessarily egotists, but they have an egotistic or narcissistic approach. Maybe they just don’t know any better. They don’t leave room for other musicians to travel along with them. As a bassist, I learned this lesson intuitively. For one thing, when I started out, I didn’t have the chops that I had later on, so I had no choice but to simplify. Later on, as my facility improved, I could pick-and-choose those passages in which to lay back or step up front. I had to learn it a little more consciously with the blues harp and the guitar, but as soon as I started laying back and stopped showing off with the blues harp or dominating the moment with too much rhythm guitar, my playing jumped up a level, was more rhythmic, and it was more fun as well. “Exercise mind and body control… don’t think about it. Allow it to happen. This is the time for ‘not concentrating’.” What you “intend” to do is different than what you may be “trying” to do. This is basic Yoda-101: “There is no try, there is only do”. For instance, don’t “try” to learn a part or a song, just “do it”. As far as the “not concentrating” is concerned, don’t worry about what you can or cannot do technically. Let it go and go with the flow. Chances are you’ll be learning on the fly and play better than you did previously. “Play me (Music) all you want, but you must know this: it is only when you allow >me< to play >you< that you will know me completely because then we will be one and the same.” This is airy-fairy new-age-speak about getting in “the zone”. All musicians seek that magical experience of letting the energy of the universe flow through them, or into them, or in and out of them, or whatever it is they think is going on when they find themselves in “the zone”. You don’t even need to warm up before a performance if you know how to get there already. Are you confident that this will happen shortly after you begin playing? When I perform, I know where “the zone” is and don’t hardly need any warming up. Not everybody is like that—most people need to get warmed up before they get in “the zone”. If you already know where the zone is, there’s no particular reason that you won’t get there almost instantly. My ability to get in “the zone” is why I almost always sing the first two songs of the first set with my bar band, the CBDs. This is not true for everybody, though, and I’ve always wondered why that was the case. “Don’t try real hard, try real easy. Treat it like a game.” They don’t call it “playing” for nothing. If it isn’t any fun, you shouldn’t be doing it in the first place. If it feels like work, something wrong is going on. In many ways, music is, as Wooten claims, a game or a puzzle. “Play quieter to make (an audience) listen…When you’re playing to an inattentive audience, you and your bandmates are the background noise… you can make them listen without their even knowing it. The best way to do that is through dynamics, or even better, through space. Create silence…Learn how to make a rest speak louder than a note. Play a musical line and start leaving notes out, putting the emphasis on the rest.” Dynamics is about varying the volume and intensity of different parts of a piece, and “space” refers to the empty spaces between notes. Both are essential to making music work effectively. This is, again, about leaving space for both the “Music” and the other musicians. Moments of silence between notes keeps rhythmic parts more well-defined and leaves spaces for other sounds. This is essential in most improvisation. If the music remains at the same volume throughout, it can generate ear-fatigue and eventually become nothing more than background noise or Muzak. Note the predilection of grunge bands to contrast quiet contemplative sections with raging mania from one verse to another. Perhaps they learned this trick from the bombastic classical composers of earlier generations. “(Frogs) listen all right, better than most humans do…Each animal made a sound that somehow supported the other sounds while leaving enough space for all to participate.” Wooten may overstate the ‘ability’ to communicate with animals, especially when a frog hops up onto his knee and a deer rubs her moist nose on his cheek, but animals do listen. I have had numerous conversations with ravens, swallows and swifts in the Utah canyon-lands over the years by mimicking their calls on the baroque recorder. It certainly attracts their attention and they definitely have something to say about it. They don’t seem interested in the blues harp at all. The chorus of frogs that Wooten talks about is a good metaphor for a band context, the leaving of “enough space for all to participate” and listening to one another to find the right places in which to play. “Most musicians seem to reserve their ears for themselves rather than open up their ears to the rest of the band.” This is because most musicians are worried that their playing is insufficient and it’s all they can do to keep up… or they want to show off their fabulous chops. Either way, it is an egotistic and narcissistic mistake not to listen to the rest of the band. Once you open your ears, you are in position to make both yourself and all the other musicians sound better. Not every song needs to feature YOU above all others. When you make the musicians around you sound better without self-aggrandizing grandstanding, you’re really getting it. “Practice while you play so that you can make the most of both…Music should not feel like work. If it does, you know you are going about it the wrong way.” Or make practice play… remember, it should always be fun. You can ‘work’ on stuff without feeling like you’re at ‘work’. If it’s not fun, why would you even bother? I suppose this is easy for me to say. As a hobbyist who dabbles in professional music, I’ve never had to make my living from it. Walls Of Genius certainly kept me busy and at a certain point I became admittedly overwhelmed. But I was never forced to work so hard, promoting and performing endlessly, that music became like a “job” to me. I would advise anybody making music, from the total amateur to the professional, to keep as much “fun” as possible in the picture. When the performer is having fun, the audience is, too. “Music is a part of who you are.” In a way, you are a conduit for “Music”. At its best, it flows through you, energizes you and takes you to ecstatic heights as both a listener and a musician. It must be a part of you always if you are to appreciate it as fully as possible. “When have you ever truthfully said ‘thank you’ to your (instrument of choice)?” This was a new one to me. I had never before “thanked” my bass, my guitar, my harmonicas. But really, they deserve our thanks. We work them really hard when we play them. Some of us maintain them very carefully, cleaning and polishing, changing strings and all that. But thanking them? Hey, it couldn’t hurt. We always thank our audiences, don’t we? Gratitude is a good thing. We wouldn’t even be on stage if there was no audience who wanted to hear musicians getting in the groove. So thank you for reading this… And thank you, Fender Jazz Bass for facilitating a life in “Music”.

21 Comments

|

Archives

January 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed